More than one quarter of older American workers earning higher wages — above $137,700 — have nothing but Social Security to rely on in retirement. And nearly half of all families have no retirement savings at all. If forced to retire early due to job loss or ill health, more than 70% of Americans have no back-up plan. According to Teresa Ghilarducci’s research, just 21% of people aged 62-70 have sufficient resources to maintain their standard of living in retirement.

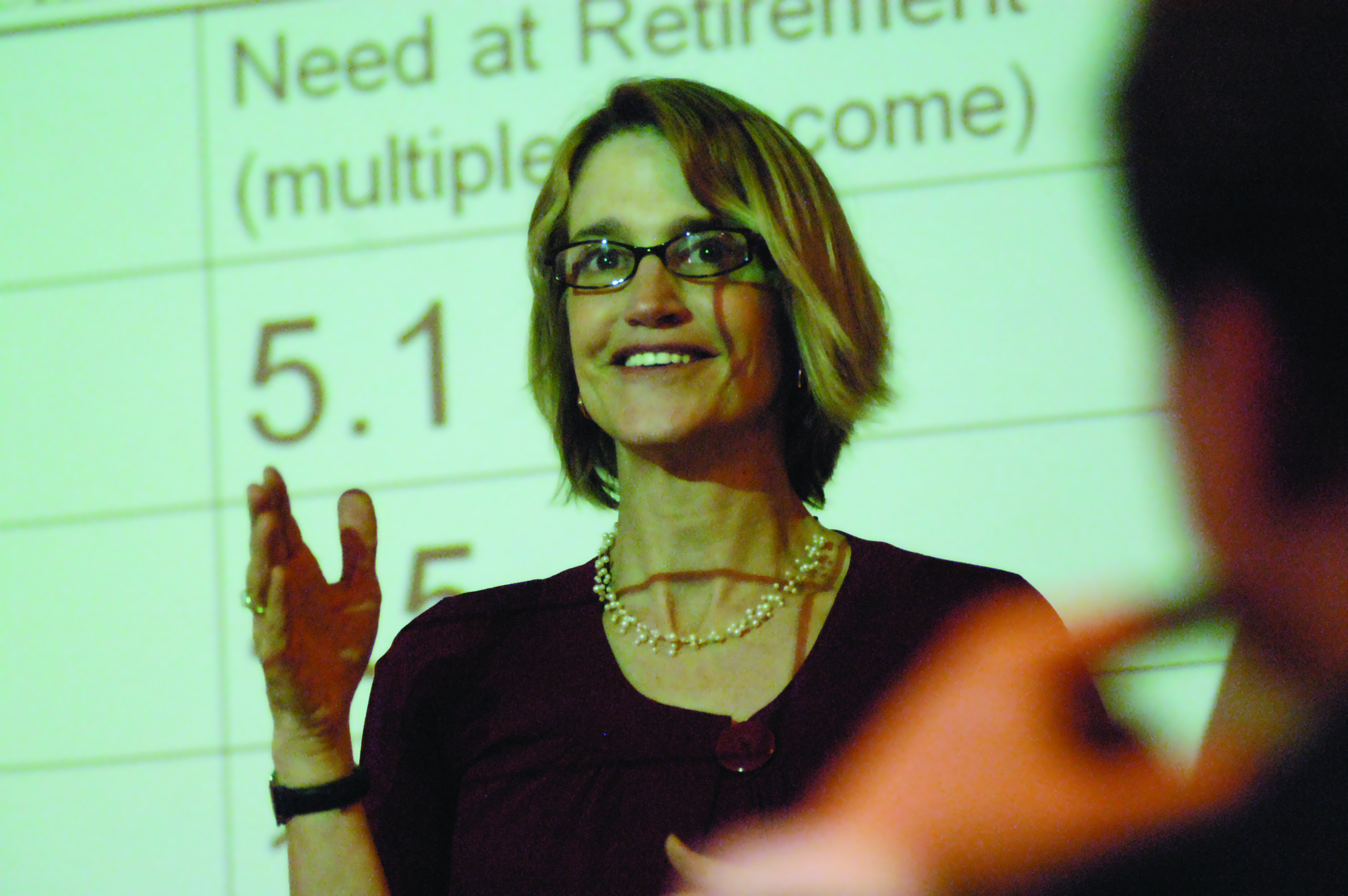

Teresa Ghilarducci is the Bernard L. and Irene Schwartz Professor of Economics at the New School for Social Research in New York City and the director of the Schwartz Center for Economic Policy Analysis and The New School’s Retirement Equity Lab. She has twice served on the advisory board of the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation. A prolific author and nationally recognized expert on retirement security, her latest book is “Work, Retire, Repeat: The Uncertainty of Retirement in the New Economy.”

In it, she argues that Americans should change the way they think about and plan for retirement. She finds that working longer does not close the gap for people who are not prepared financially for retirement. She makes the case that for people who need to continue working past a normal retirement age because they lack the resources to retire with an income that places them above the poverty line, working longer means aging more quickly and dying sooner.

Furthermore, keeping large numbers of older people in the workforce in low-wage jobs depresses wages and benefits for other low-wage workers, though it benefits employers in retail, fast food, home healthcare, and janitorial services.

Among wealthy nations, the U.S. is one of the few without a universal system that requires them to save enough for retirement. Nearly 50% of private sector workers lack access to an employer-sponsored retirement plan. Even in what we might have consider the heyday of the defined benefit plan several decades ago, a huge percentage of Americans were not covered.

If the rise of defined contribution plans fueled a retirement income crisis in the U.S., then I’m partly to blame. In the late 1980s and early 1990s I was responsible for marketing 401(k) and 403(b) plans to employers and employees for a large asset management firm. I didn’t realize at the time that the growing use of defined contribution plans would result in so many employers freezing or terminating defined benefit plans, transferring the risk of saving enough for retirement from employers to their employees.

But DB plans aren’t a panacea. They’re complicated and expensive to administer, and so tend to be the province of large employers with unionized workforces. They also benefit people who stay for decades with one employer. That is not how people arrange their careers today. The self-employed, people who change careers or employers, and people who work for small businesses could work a lifetime but not be covered by a DB plan. People in the startup world would be out of luck.

Teresa proposed a solution to this problem, originally called a Guaranteed Retirement Account (“GRA”), to which all workers and employers would contribute 3% of pay, in addition to making contributions to Social Security. They could contribute more if they like. These accounts would be owned and controlled by the individual. The principal amount would be guaranteed. Distributions would come in the form of annuity payments to ensure that retirees don’t outlive their savings.

Q. Teresa, how should we think of Social Security? Is it an insurance policy? One of three legs of your retirement income stool? Or is it an annuity on which you can comfortably live in retirement? What should it be?

A. Social Security is a hybrid program. It’s a social insurance program. The insurance part is that all workers pay a premium and they will get collection of a stream of income if they confront a risk. It’s just like auto insurance and health insurance. We all pay premiums, and we only collect if we have a contingency. You may collect on your health insurance if you have cancer but we don’t collect if we are healthy. Car accidents: we collect nothing from our insurance if we have perfect luck and a perfect driving history; we collect a lot if the worst happens to us.

Social Security is the same. The contingencies in Social Security are disability, dying and leaving behind dependents, or having the contingency of retirement. It provides a stream of income when you lose your labor income.

So it’s insurance, but it’s insurance structured so that lower income people, people with great need, get relatively more from their premiums paid than richer people. The replacement rate for a retiree who worked in a low wage job for most of their life is higher — there’s a higher return for their premium dollar than for someone who worked for $1 million per year for 40 years. But we don’t usually think about rate of return when we’re talking about an insurance policy.

It’s an insurance policy with big protections for the most vulnerable.

Q. How does what the average person puts into Social Security compare to what they take out?

A. The average person gets more than they put in because, as with all life insurance, there’s a mortality credit. People who die early and without dependents are actually helping — they leave behind assets for the people who live a long time or who have a lot of dependents. There’s a redistribution that goes on within any pooled insurance product. Those people who survive get more than they put in. People who are very high income and who die without dependents are the group that gets less dollars than they put in. But we don’t have to insure that because they don’t experience any harm. But most people get more than they put in.

Q. Until just recently, Americans have been living longer. To what extent are those longer lifespans placing a strain on Social Security?

A. Two things in that question. One is that not everybody is living longer and not everybody has experienced an improvement in their expected lifespan. White women hardly had any improvement in their expected lifespan. People without college educations surprised the Social Security actuaries and have shorter improvements in their life span than was predicted. White men have seen most of the improvement in lifespan because they stopped smoking and have received good cardiac care. But all in all, the actuaries were not surprised by the mortality and longevity statistics. Those trends have not disturbed Social Security finances.

So, you might ask me what has created a shortfall for Social Security? There are two things, but they really just add up to one thing, which is that greater than expected earnings have escaped the payroll tax. The actuaries had not anticipated such lopsided wage increases, meaning that wage increases have gone to almost everyone at the top of the income distribution, and because of the earnings cap that money escaped the Social Security system. Actuaries had presumed that all workers would get the same kind of wage increases, and then that helped predict how much money was going to go into Social Security, and they were caught flat-footed by most of the earnings increases going to the very top.

The other way that money escaped the Social Security system is that a lot of money went into healthcare. Healthcare cost increases and premium increases meant that workers weren’t getting wage increases. They were having to put all their productivity gains into their healthcare plans, and those premiums escaped the Social Security system. So, a lot of earnings escaped the Social Security trust funds.

Q. Should we remove the cap on earnings taxed for Social Security, and would that raise enough revenue to fund Social Security beyond 2033/4/5?

A. Yes. We’ve been looking at this since we’ve had a cap, and the answer 20 years ago was no, it wouldn’t be enough.

But it’s now enough. In the last five years, the projections show, as earnings have continually gone to the top, there’s so much money there that eliminating the cap would not only solve the solvency problem, but there’d actually be a little left over to bring up the very bottom and eliminate poverty. It’s kind of easy, and the rich might grumble a little, but they wouldn’t grumble too much if, in fact, it meant an end to old-age poverty. We have previously raised taxes on the rich for Social Security without a peep of complaint. That was when we lifted the cap for Medicare contributions. In the realm of wicked problems in public policy, this one is not a wicked problem. It’s easily fixed.

I want to bring up one thing about Social Security. This is an area where we don’t have talking heads debating about the numbers. The right wing and the left wing, the up wings and the down wings — all the wings, all the faction — actually agree on the numbers. They trust the Social Security actuaries’ numbers and that’s really rare in a policy debate. There might be ideological differences between them, but there aren’t numerical differences.

Q. Alicia Munnell, of Boston College’s Center for Retirement Research, and Andrew Biggs, of the American Enterprise Institute, have proposed eliminating the tax deferrals individuals receive for contributing to their 401(k) accounts in order to shore up Social Security. They believe people would continue to participate in these plans in the absence of the tax break. I disagree. Your thoughts?

A. Two thoughts. The overall thought is that she is kind of right, though she did not take into account the kind of behavioral response that you are positing very explicitly in the most recent version of this proposal.

This proposal has been out there since I was in graduate school. She wrote about it in like 1979 and I remember citing it my dissertation. It has been well known among the community that there was a potential response to the tax breaks for retirement savings which is that people who can will just shift around their portfolio. There’s always been this concern that they will just take money from their taxed accounts and move it to the tax deferred. It was an empirical question, whether or not they do that. And she has come down, on the evidence, that that is in fact what has happened. The bulk of savings that are in these retirement accounts would have been saved anyway but in taxable accounts. There are a couple of methodologies which she has looked at that have come to that conclusion.

But I don’t think you’re wrong either. Some money will go away. Maybe not a lot, but absolutely the theory and practice would say that some middle-class people wouldn’t get the advice from their tax accountant to put money in their SEP. I think I would be in this category, and I’m a retirement expert since I was 19. I’m an extraordinarily forward-looking and financially literate person, but if my tax accountant didn’t tell me to put $17,000 in my SEP, I might have bought a watch, or a lot of watches for me and my friends. I’m human, too. On the margin it would happen, but probably not to the extent you fear.

But her proposal is really making another point. She’s not trying to solve Social Security. She would be in favor, and has always been in favor, of raising the cap, because that’s where the billions and trillions are. She’s making the point that the tax breaks for retirement plans are top heavy and not very effective. Bottom line, I totally agree with her.

Q. How would you change the tax code so that the greatest incentives to save for retirement go to those with the lowest incomes, not those with the highest incomes?

A. So, Jim, that’s easy. I have a full-bodied complete and vetted plan. It’s now a bill in Congress. It’s based on a white paper that I wrote with Trump’s top economist. We met on the field of PhD. Economists. We didn’t meet on the political field. We crossed the room to be together as PhD. Economists, because if we were at a cocktail party in D.C., we would never have crossed the room to talk to each other. But we did find a place to come together.

It’s called the Retirement Savings for Americans Act (“RSAA”). It keeps the expensive tax breaks for your people (and for you and me) so we’re not taking anything away from people. And we’re adding a refundable tax credit to supplement the 87 million workers who don’t have a retirement plan — gig workers, left behind workers, workers who have come in and out of the labor force because of care work. So I would add to the tax code and have a matching credit from the federal government to people’s retirement plans.

If Congress wants to pay for it, I know the place where we can do it. That would be by trimming back the subsidies for the very highest income workers. Because you and me, and my dean, and the president of Blackstone would be saving that amount for retirement anyway.

Q. According to the Census Bureau, in the U.S., children are more likely to live in poverty than people 65 and older. Given this, is it fair to direct additional tax dollars to this older cohort which already receives Social Security and Medicare?

A. So, in my book, in chapter eight, I mention that one of the myths is that if we spend less on the elderly we’ll spend more on children. That might work on a spreadsheet where you move dollars around and you have a fixed pie, but that’s not the way politics works. I’ve found (and it’s in the book) that over 30 years and in 163 countries, the countries that spend the most on the elderly also spend the most on children in terms of the fraction of GDP. That’s because if there’s a social democratic coalition to help protect the vulnerable then it has enough political power to make sure that children get educated pre-K, that there’s a childcare tax credit, and old ladies get a pension.

In reality, there aren’t those dollar tradeoffs. If the forces that want to cut Social Security were in power, they would not be giving a childcare tax credit or lifting black children out of poverty.

Facts can change my mind. There may be a point where we can’t afford to do both, but the facts on the ground show that we don’t spend anywhere near our counterparts for children and the elderly. And if you look at the OECD, Jim, and use those standardized poverty numbers, the U.S. now has a higher poverty rate among elders than we do among children. Now, that may be temporary because of the huge effect of the child tax credit from the pandemic era. Also, the Social Security cuts are kind of creeping in. We also had a lot of layoffs of youngish older people (early 60s), so many had to claim their Social Security early. So it kind of flipped, where the elderly poverty rate went up much higher than for all the other groups. I think that census data might be a little bit off.

Q. Am I right in concluding that you are not a fan of individual retirement accounts?

A. I have called them a failure. And I’ve gotten death threats for it.

I would like at this moment to temper those comments. The 401(k) system has worked well for some people. But for the vast majority of people, they don’t help them save, they don’t help them invest well and efficiently, and they don’t help them distribute the money they have saved securely and for a lifetime, which are the three things a retirement plan has to do. Otherwise, they’re fine.

They have provided wealthy people with a tax deferred way to save for themselves and their heirs. Not really a goal of public policy, though. But they have done well for the very luckiest.

# # #